As one of Northeastern’s newest faculty members, cognitive neuroscientist Jonathan Peelle is still setting up his lab. But he is already unpacking advice.

Protect your hearing, Peelle says. Once damaged, its function cannot be fully restored, and that has important implications for speech comprehension.

“You don’t have to have profound hearing loss to have cognitive challenges,” says Peelle, whose research on the neuroscience of communication, aging and hearing is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Even mild hearing loss causes the brain to work harder to understand speech, especially when background noise is involved, he says.

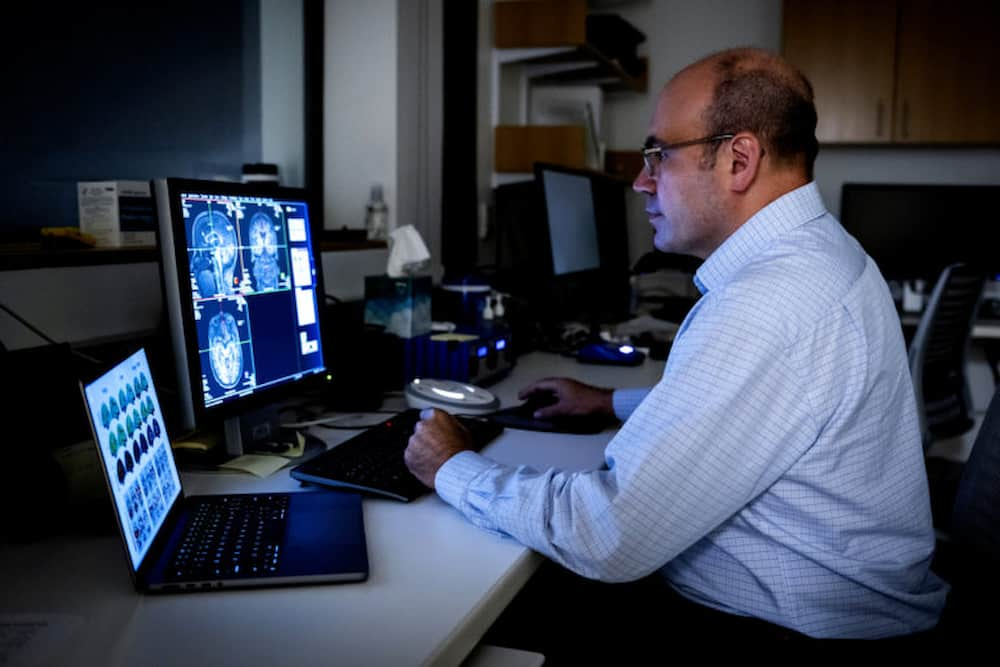

He uses functional brain imaging to measure tiny changes in blood flow to the brain of subjects with mild hearing loss and individuals with cochlear implants.

Peelle, an associate professor at Northeastern’s Center for Cognitive and Brain Health, also employs a lab technique called pupillometry, which measures minute fluctuations in pupil diameter.

08/26/22 – BOSTON, MA. – Jonathan Peelle, cognitive neuroscientist in the Center for Cognitive and Brain Health, conducts research in the ISEC building at Northeastern University on Aug. 26, 2022. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

Pupil diameter gets bigger when people listen to challenging speech, Peelle says. Add background noise, and “your brain might have to work harder.”

“If I can help your hearing, I’m going to help your cognition,” at least in the short term, Peelle says.

Large population studies, such as a 2020 report published in the medical journal Lancet, show that dementia is more likely in those with hearing loss.

But the risk for individuals has not been quantified, Peelle says.

“No one’s drawn that link yet,” he says.

Peelle, who comes to Northeastern from Washington University in St. Louis, says he is excited to work at a university that has a community-based audiology clinic.

He says in the future it would be interesting to measure to what extent hearing aids reduce cognitive challenge, with an eye toward improving the devices.

“There really have been very few studies showing how much cognitive benefit people have developed from hearing aids,” Peelle says.

Peelle’s interest in helping people understand brain function has extended to hosting two podcasts. He started The Brain Made Plain while at Washington University to give students exposure to neuroscientists.

“I wanted them to get to know some other scientists as people,” Peelle says.

“We try to explain terms and not be too sciency about stuff,” he adds.

Peelle also co-hosts The Juice and the Squeeze with Carleton College professor Julia Strand. They share information on the ins and outs of careers in science, what it’s like to apply for a grant, give a scientific talk and apply time management skills.

The podcasts have been more occasional than steady recently, Peelle says, with life changes including the new job at Northeastern and the growth of his young children— a 6-year-old daughter and 2-year-old twins.

The adjustment to New England has been relatively smooth since his wife’s family is from Boston and Peelle obtained both his master’s degree and Ph.D from Brandeis University.

“Boston is kind of a second home for us. We are thrilled to be here,” Peelle says.

Peelle also has a Twitter presence noted for both gentle humor and sharing the work of other scientists.

He’s been on the social media platform since its inception nearly 17 years ago.

“I actually found out about the job at Northeastern because one of the other faculty members tweeted about it,” Peelle says.

As a graduate student, he says, his initial interest was on speech and how it was affected by age-related changes in cognition and language processing.

After a few years, his attention also turned to hearing.

“We’re looking at language processing, but it has to come through the ears,” Peelle says. “It’s a holistic view of how we communicate across the life span.”

“A lot of what I preach about is hearing protection,” he says. He urges people to wear earplugs during rock concerts, for instance, and to take breaks so they are not listening for a full three hours.

“Hearing damage,” Peelle says, “is a combination of how loud things are and how long you listen to them.”

He says he has spent the last 10 years studying why speech comprehension is difficult for some people.

“I want to spend the next 10 years making it less difficult.”

This post was originally published on News @ Northeastern by Cynthia McCormick Hibbert.